Hervé Barrier, co-leader of Highland Park NPSNJ Chapter, one of the curators of the Rutgers 2023 Personal Bioblitz project, and a passionate contributor to the iNaturalist project (id=hb2000) wrote to encourage us all to join the Rutgers 2023 Personal Bioblitz. Click here to join: https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/personal-bioblitz-2023

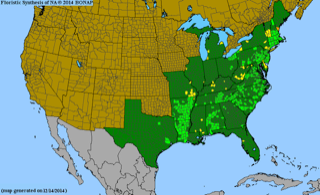

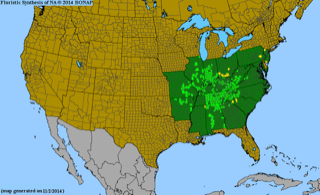

Every spring, Rutgers organizes an online Bioblitz (a species survey) using INaturalist. This year’s Bioblitz just started and will continue until mid-May. This time window is particularly interesting because of the emergence of spring ephemerals. Rutgers students, faculty, alumni, and friends and nature lovers (which means you, NPSNJ members!) are invited to join the project.

What is Inaturalist.org?

Fun and educational, iNaturalist is a world-wide citizen-science tool used by universities, nature groups like ours, and individuals. Anybody, beginner or expert, can report observations (picture, audio) of plants, birds, insects, mushrooms, any organism, or evidence of it. The huge amount of collected data is used by scientists, land planners etc. In schools, it encourages students to observe nature, develop identification skills or do specific studies. You can use a smartphone (or a camera and a computer). If you don’t know the name of a species, other people will help. If a species should be protected, you can easily obscure its location. iNaturalist is also a great way to learn about species. It has a sophisticated identification algorithm and can help you identify species in the field, or at least make a good guess that other iNaturalist members can help narrow in.