We have had a massive hacking attempt in which a criminal ran 16,000 credit card numbers on our site. We contacted the software vendor whose plug in was used to do this and have taken our donation form offline for a week or two as we rebuild the donation system from scratch to prevent abuse in the future.

2024 NPSNJ Bioblitz

April is Native Plant Month!

Hervé Barrier, NSPNJ Highland Park/Middlesex County Chapter leader has created an iNaturalist.org project called ‘Native Plant Month 2024 – NJ‘

This is a BioBlitz, it follows the 3-unity rule:

- unity of time: April 2024

- unity of place: NJ

- unity of action: photograph as many native and non-native plant species as possible and post the observations on Inaturalist.org

iNaturalist.org is a free, worldwide, educational Internet tool allowing anybody to report wildlife species (including plants), and allowing scientists to use the resulting data. Universities are big users of it. With iNaturalist, anybody can report any species, anywhere in the world, all year long.

The ‘Native Plant Month’ project will be open for observations only during April. During this period, we can all go to parks or our backyard, take pictures, post them in iNaturalist, and add them to the project.

The objective is to report as many native species as possible and to get as many people involved as possible (everybody is a naturalist!). Anybody can participate (members, non-members, family, friends, friends of friends, etc.). Non-native plants can be reported as well since in many cases we don’t know if it is native or not until the identification has been ascertained.

What to do:

- before April, become an iNaturalist member and practice reporting plants, animal, mushrooms, etc.

- before April, join the ‘Native Plant Month 2024 – NJ’ (note you cannot add observations until April).

- in April, add plant observations to the ‘Native Plant Month 2024 – NJ, ‘ project

Be safe and enjoy nature.

Go to iNaturalist.org to find out more.

Notes:

If the species is endangered or you do not want to reveal the location (e.g., it is in your backyard) you can ‘obscure’ its location

As NPSNJ recommends, take all safety precautions when in nature (e.g., ticks are present all year round).

Advocacy Alert: Check Your Town’s Tree Removal and Replacement Ordinance

The Advocacy Committee of the Native Plant Society of New Jersey (NPSNJ) has learned of an important issue that has been receiving little public attention.

What’s Happening

New Jersey towns are now required to pass ordinances governing tree removal and replacement per municipal stormwater permits (MS4).

Guidance is being relayed via a model ordinance developed by the DEP, but this guidance doesn’t address the use of natives rather than non-natives, exotics or invasives, nor how to develop a sufficiently broad list of allowed replacement species.

The Context: New DEP Requirements

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) instituted a new requirement in November 2022 that all NJ municipalities adopt and enforce a community-wide ordinance covering tree removal and replacement, if they didn’t already have an ordinance that met the requirements. This rule is part of NJDEP’s efforts to manage stormwater runoff, particularly in the face of climate change. The tree ordinance is required as part of the permitting process for the discharge of stormwater from municipal storm sewers.

To assist municipalities in this process, the NJDEP issued a model tree replacement/removal ordinance, which is available on the NJDEP website. Unlike some of the other model ordinances, the model tree removal and replacement ordinance developed by the NJDEP is not required to be adopted as is. It was provided as a template that municipalities could use to meet the requirements of the permit. Municipalities can develop their own ordinance or use/update existing tree ordinance to meet the permit requirements.

The essence of these ordinances is that anyone who wants to remove a tree, even from private property, must replace it with a tree of a similar trunk diameter or multiple smaller trees. (The ordinance includes a locally developed list of replacement trees as Appendix A.)

The Unintended Consequences: Ordinances That Limit Tree Species

Each municipality must include this appendix listing trees that are acceptable as replacement trees, or at a minimum listing trees that are not acceptable. Lacking sufficient knowledge about ecology, many municipalities are developing extremely short lists of acceptable trees—often as few as a dozen—that do not allow for broad biodiversity and may even include trees that are not suitable for the ecoregion. In some cases the lists include exotic and invasive species.

The New Jersey Association of Planning & Zoning Administrators (NJAPZA) is providing additional information via a webinar series for planners and others who are assisting in the preparation of these ordinances. In these sessions discussion encourages biodiversity, but also focuses on non-native species often considered better at surviving urban/roadway (street tree) environments.

We thus encourage members of NPSNJ to check their municipalities’ tree removal and replacement ordinances, looking for the following concerns:

- Narrow lists of approved replacement trees. Is the list of approved replacement trees (which normally appears in an appendix) broad and inclusive enough? Does it represent the diversity of tree species that are native to your area? Does it include species for different conditions within the municipality, such as upland areas, flood zones, swampland, or dunes? Does it include exotic or invasive species that should not be allowed?

- Considerations to allow removal of invasive species. The model ordinance regulates the removal of all trees. Does your town’s ordinance have any special consideration for removing invasive species of trees? One simple solution is for the ordinance to allow for invasive species to be removed, without restriction.

- Size considerations for planting tap-rooted replacement trees. The ordinances will require that removed trees be replaced with trees of a similar caliper or by multiple trees of smaller caliper. However, many oaks, and other trees that grow a tap root, will be healthier and grow faster if they are planted when very small. Exceptions should be made to allow for the size of replacement trees to be small when planting tap-rooted trees. Consideration could also be given to providing credit for trees planted during a period of time prior to removal in anticipation of future tree loss.

If your town’s tree removal and replacement ordinance is lacking, we encourage you to contact your local officials to ask them to amend it.

Listed below are resources to help identify appropriate trees for your municipality or ecoregion:

- Lists of trees native to New Jersey counties can be found on the Native Plant Society of New Jersey website.

- A list of invasive trees that should not be planted can be found on the New Jersey Invasive Species Strike Team website.

- The cooperative extension for your county can provide additional helpful information.

The due date for towns to adopt these ordinances was recently extended to May 1, 2024. Many towns have already completed the process, but ordinances can be amended at any time. And of course, if your town has not yet finalized its ordinance, you can provide input to help them get it right the first time.

Learn more! The New Jersey Association of Planning & Zoning Administrators (NJAPZA) has organized a series of three free webinars on the tree ordinances. The recordings of session one can be found here:

Session One recording (password: Session#1)

Session Two recording (password: Session#2)

Learn about Beech Leaf Disease with Ecologist Jean Epiphan

Jean Epiphan, Agriculture & Natural Resource Agent (Assistant Professor) of Rutgers Cooperative Extension in Morris County spoke to the Somerset County Chapter about Beech Leaf Disease which is ravaging New Jersey’s beech population. This talk covers the ecology of beech, their importance in our state, and what attributes and ecological services are under threat. The basic pathogenesis will be reviewed. Then the talk focuses on steps land managers and homeowners can make to mitigate negative impacts of BLD including treatment options, cultural practices to reduce stress in beech trees, and vital steps to prepare for losses of beech canopy such as mass underplanting of indigenous tree cohorts, and management for their success.

She is a Licensed Tree Expert LTE#692 and Certified Arborist ISA NJ-1247A. Ms. Epiphan has her BS in Forestry and MS in Ecology. She has many years of practical experience working in developed and ornamental landscapes and strives to design and manage them to improve environmental sustainability as well as ecological function.

Meet NPSNJ’s 2025 Incoming Officers

Every year, at the annual meeting, the NPSNJ membership votes on a slate of officers for two-year posts. This year, we have a number of positions and some shuffling around on the board. We are delighted to announce the slate of officers as follows.

20-year career as a science editor and writer

Member of NPSNJ since 2020

Co-chair of the NPSNJ Advocacy Committee

Currently, filling in frequently as the Recording Secretary

Member of NPSNJ since 2018

Previously served as Membership VP

Co-leader of the Southwest chapter, Co-chair of the Webinar committee, Co-Webmaster, Quartermaster

Lifelong gardener awakened to native plants after reading Nature’s Best Hope; since 2017 has transformed his property into a Homegrown National Park and squirrel haven

Active with his local Environmental Commission and Green Team and regional coordinator for the Rutgers Environmental Steward program.

Elected president of NPSNJ in 2022

Board Entomologist since 2017

Founded the mail-order native plant nursery Toadshade Wildflower Farm in 1996, with a particular focus on education and the fascinating ecological diversity of the natural world

Involved with NPSNJ for many years as a member and speaker

Serves on the board of directors of the New Jersey Planning Officials; chair of the Frenchtown Planning Board

Founding member of NPSNJ

Treasurer of NPSNJ for 16 years.

Serves on the board of the Society for Ecological Restoration/Mid-Atlantic Chapter

Lifetime member of the Society of Wetland Scientists

Active member of the NJ Forestry Association, Land Improvement Contractors of America, International Society of Arboriculture, and Soil and Water Conservation Society

PhD. in History of Architecture and Urban Development. Taught at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation and Planning.

Historian, writer, and artist

Beginning in 2016, started to re-envision his property in Montclair as a demonstration of a woodland garden in suburbia

Joined NPSNJ in 2017

Founding Co-chair of the Advocacy Committee, Co-Webmaster since 2022, elected Vice-President, Membership in 2023

Vote for the Plant of the Year at the 2024 NPSNJ Annual Meeting

Make your Plant of the Year choice known at the 2024 Annual Meeting. All in-person and virtual attendees will vote for one nominee in each category – Rare & Unusual and Backyard Perennial. Join us, see great speakers, have breakfast and lunch with other members, and vote for the Plant of the Year!

Nominees for 2024 Rare Plant of the Year

Text by John Suskewich

Cypripedium acaule

Pink Lady’s Slipper

Seeing Pink Lady’s Slipper on a walk in the woods, sometime in May, a plant lover’s endorphins really kick-in. The pink and tan flower has an unusual moccasin shape and dangles from a stem that rises from a pair of veined basal leaves. It has a unique design feature for pollination by bumblebees, which requires them to follow a one-way path through the flower, forcing insects to take a pre-determined route past its reproductive parts, sort like the way Ikea makes you travel past all their sales displays before you get to the exit. Cypripedium acaule is not common but can readily be seen at various places in New Jersey, such as near Ramapo Lake in Bergen County and at Cheesequake Park near the center of the state.

Photo credits:

(1) John Lynch, Native Plant Trust

(2+3) Hervé Barrier

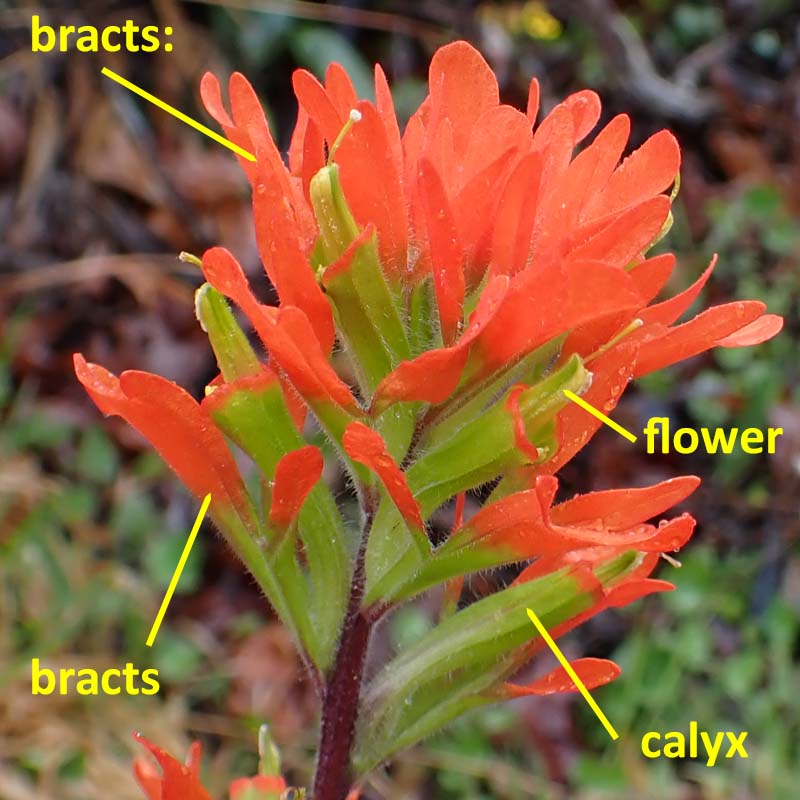

Castilleja coccinea

Scarlet Indian Paintbrush

This biennial plant is one of the few New Jersey representatives of the Orobanchaceae or “broomrape” family. (not my idea) According to MOBOT, it is primarily found “in prairies, rocky glades, moist and open woodlands, thickets and streambanks” What look like flowers are actually very bright, very colorful, very vermilion bracts that contain the actual flowers which are tiny and greenish. Because it is semi-parasitic and grows best near a companion plant, Scarlet Paintbrush is reputed to be tough to establish in a garden, but it is striking, vivid and probably worth the effort. Sounds like seeing it growing in the wild would be worth the effort too, even if it meant getting tangled up in a razor wire of wild greenbriar.

Photo credits: Millie & Hubert Ling

Platanthera integra

Yellow Fringeless Orchid

Platanthera integra, Yellow Fringeless Orchid is a very rare, exceedingly exquisite denizen of the acidic swamps and bogs of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens. From mid-July to mid-August from a base of small narrow leaves, this gem sends up a stem a foot and a half high, clothed in a few more small narrow leaves, and topped with an inflorescence maybe 3” long of delicate, fringeless! (unlike some of the other representatives of this genus) yellow to orange flowers. Always uncommon, its population decline over time has been attributed to habitat loss, especially fire suppression practices that allow it to become “shaded out.” This is another orchid pollinated by bumblebees.

Photo credit: Millie & Hubert Ling

Ribes missouriense

Missouri Gooseberry

Ribes missouriense, the Missouri Gooseberry, is a native, ornamental, deciduous shrub that in summer produces a small fruit, edible after you dump enough sugar on it, like other gooseberries and currants. The plant grows about three feet high, prefers at least some sun, has lobed palmate leaves, and wields sneaky, nasty thorns along the arching stems that’ll scratch you good like an clawed cat. It can be found in thickets, near wood edges, and around dry glades. The flowers are small, clustered, and drooping, and are followed by tart green fruits. Maybe you can make a kind of cassis out of them like my grandmother made with blackcurrants (also peach pits and dandelions.) Probably not a candidate for a garden since it’s considered an “alternate host for white pine blister rust” like other Ribes.

Photo credit:

(1) Toadshade Wildflower Farm

(2+3) Wikimedia Commons

Nominees for 2024 Backyard Perennial of the Year

Text by John Suskewich

Lobelia siphilitica

Great Blue Lobelia

Lobelia siphilitica, Great Blue Lobelia, is the blue brother of remarkably red cardinal flower, L. cardinalis. They are both part of the very garden-worthy bellflower family, Campanulaceae. In the wild, where it is thrilling to come upon, Great Blue Lobelia is most often seen in part sun to part shade, near streams, sloughs, and other wetlands, telling you that in the garden it prefers moist soil. Where content, it attains a height of two to three feet and colonizes through self-seeding. In most gardens, it persists for years. The summer flowers of Great Blue Lobelia are various shades of violet-blue, lipped, lobed, and arranged on a long stalk. They are an important food source for several native bees, bumblebees, and hummingbirds.

Photo credits: Mary Free, Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia

Conoclinum coelestinum

Blue Mist Flower

Conoclinum coelestinum, Blue Mist Flower is a very pretty plant that looks like a blue boneset or snakeroot, or a hardy, taller version of the annual ageratum sold in garden centers. Conoclinum coelestinum blooms late in the season, is very easy to grow, and adds a touch of sapphire to the fall flower palette. Height can be a foot or two, and breadth, well, one almost fatal flaw of this plant is its aggressiveness, because where happy it spreads through rhizomes and self-seeding. If you are good at weeding or have other aggressive plants that can duke it out with mistflower, it’s worth having. It attracts many native autumn pollinators: bees, butterflies, and skippers, and displays a strong degree of deer-resistance.

Photo credits:

(1+3) Michael Jacob

(2) Flower – September – Wake Co., NC, Cathy DeWitt, CC BY 4.0, North Carolina Extension Plant Toolbox.

Hibiscus moscheutos

Swamp Rose Mallow

Hibiscus moscheutos, Swamp Rose Mallow is the gorgeous, hardy native relative of the gorgeous tropical hibiscus grown in greenhouses. In its natural setting, Swamp Rose Mallow is found in sites that range from moist to wet, but established garden plants can handle average soil, unless there’s a drought when a glug from the hose might help. This hardy hibiscus luxuriates in the torrid days of summer, and in some years the new growth doesn’t even emerge until June when the days really, really start warming up. The salad plate-sized flowers are very impressive, and range in color from white to deep pink. The plant itself can attain heights of over six feet, and it has a few pest problems, notably Japanese beetles. Other gardeners in the neighborhood will drool with envy at your well-grown specimen of Hibiscus moscheutos.

Photo credits:

(1+3) Michael Jacob

(2) Native habitat, Chris Kneupper CC BY-NC 4.0, North Carolina Extension Plant Toolbox.

(3) Seed Pods – February – Wake Co., NC, Cathy DeWitt,

attribution: CC BY-NC 4.0, North Carolina Extension Plant Toolbox.

Opuntia humifusa

Eastern Prickly Pear Cactus

Opuntia humifusa, Eastern prickly pear has a real high cool quotient. One of the few hardy succulents native to New Jersey, it needs to be sited carefully in a very well-drained location, in gravelly or sandy soil, preferably in full sun. The height is usually less than a foot as the pads, which are swollen stem-segments, not leaves, are pretty prostrate. Probably not a good plant where curious kids hang out because those pads are covered with tiny little bristles that can stick to your skin and are really annoying.

The lovely yellow flowers open in June and July, each lasting but a day or two, and are followed by an edible fruit that Native Americans ate, either fresh or dried. In the Ramapo Mountains, above Hawk Rock, there is a spot called Cactus Ledge, a sunny glade covered with this plant that in early summer is a sight to behold.

Photo credits:

(1) Kazys Varnelis

(2) Wild Ridge Plants

(3) Douglas Goldman, USDA, CC BY-NC 4.0, North Carolina Extension Plant Toolbox.

(4) skdavidson, CC-BY-SA 2.0, NC Cooperative Extension and NHC Arboretum

Governor Murphy Vetoes A3677, NJ’s Invasive Species Bill

We have a disappointing update to A3677, the NJ Bill to prohibit the sale and traffic of invasive species. Governor Phil Murphy has vetoed it under the rationale that the Department of Environmental Protection needs to be more involved in the drafting of the bill. For a bill of such critical importance to our state’s ecology, it is surprising that Murphy and the DEP did not work more closely with the Assembly and Senate and instead punted the work back to them for another year. Although an override is possible, as the bill had unanimous and bipartisan support in both houses, it is unlikely given the late date We will be advocating to send the bill back in front of both houses when the new session starts. Read his statement here.

2023 Advocacy Update and Call to Action on Invasives

Happy New Year!

The Advocacy Committee of the Native Plant Society of New Jersey is excited to report on our progress in 2023 to protect the native plants of New Jersey and to look ahead to new legislation. Your participation, by contacting the governor and legislators, will make a difference.

Bill to Ban Invasives – Finally on the Governor’s Desk

For the last two years, we have been working to pass New Jersey Bill A3677/S2186. This bill aims to prohibit the sale, distribution, or propagation of certain invasive plant species and establishes the NJ Invasive Species Council. It’s a crucial step toward controlling invasive species and protecting our native plant ecosystems. In the spring of 2022, we pushed to move this bill forward when few had faith in it. In December 2022, our committee co-chair Laura Bush testified about it before the NJ Senate Environment and Energy Committee and again before the Assembly Agriculture and Food Security Committee in May 2023. The bill finally passed both houses with unanimous support last week and now we are delighted to announce that it is on Governor Murphy’s desk. Even though this bill had bipartisan support in both houses, this does not mean the governor is certain to sign it. Please reach out to the governor via the governor’s website (https://nj.gov/governor/contact/all/), leave a voice mail at 1-609-292-6000 or send a text message to 1-732-605-5455 and encourage him to sign it. Letters are usually better, but there is no time!

New Jersey’s State Native Pollinator

A2994/S4229, which designates the Common Eastern Bumble Bee as New Jersey’s State Native Pollinator, is another bill we are closely following. This designation underscores the importance of pollinators in maintaining the health of our ecosystems and the crucial role native plants play in supporting these species by declaring the Eastern Bumble Bee as our state pollinator. Such laws play more than a symbolic role as they encourage people to learn more about our native plants and insects and their interplay. A note to encourage your state representatives to get this bill to the floor of both houses may help make it a reality. Find your state representative and senator here.

Mikie Sherrill Bill to Promote Federal Use of Native Plants

At the federal level, HR 6832, introduced by Representative Mikie Sherrill of NJ-11, aims to prioritize and consider the use of native plants in federal projects. This bill represents a significant effort to integrate native plants into larger conservation and landscaping initiatives at a national level. Do write your House Representative and Senators Booker and Menendez to encourage them to co-sponsor this bill. Find your U. S. senators or Members of Congress here.

We continue to track other bills as they are introduced and gain support at both state and national levels.

Finally, as we look forward to the new year, we remind you to renew your NPSNJ membership if you have not already. Your continued participation is essential for the advancement of our initiatives and the fulfillment of our mission. Together, we can continue to make a significant impact on the conservation and appreciation of New Jersey’s native plants.

Thank you once again for your dedication and support. We are excited to embark on another year of meaningful work in the preservation and celebration of New Jersey’s native plant heritage.

Sincerely,

The Advocacy Committee of the

Native Plant Society of New Jersey

Receive 20 % off Tess Taylor’s new book Leaning Toward Light in time for the holidays!

This offer has ended. Members receive 20 % off Tess Taylor’s new book Leaning Toward Light in time for the holidays!

Just log in and the code will be there on your member landing page.

Caring for plants (much like reading a good poem) brings comfort, solace, and joy to many—offering an outlet in difficult times to slow down and steward growth. In Leaning toward Light, acclaimed poet and avid gardener Tess Taylor brings together a diverse range of contemporary voices to offer poems that celebrate that joyful connection to the natural world. This book reminds us how gardening is a healing practice, both for ourselves and the spaces we tend. The gorgeous hardcover package with ribbon bookmark makes this anthology a distinctive gift.

Tess Taylor, an avid gardener, is the author of five acclaimed collections of poetry, including Work & Days, which was named one of the 10 best books of poetry of 2016 by the New York Times. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The Kenyon Review, Poetry, Tin House, The Times Literary Supplement, CNN, and the New York Times. She has also served as on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered for over a decade. She will be featured in episode 8 of The WildStory Podcast.

Fall 2023 Conference Videos Online

The recording of our Fall 2023 Conference, Hidden in Plain Sight: the Outstanding Natural Diversity of New Jersey is now available for viewing on Youtube. Visit the Fall 2023 conference page here.