Make your Plant of the Year choice known at the 2023 Annual Meeting. All in-person and virtual attendees will vote for one nominee in each category – Rare & Unusual and Backyard Perennial. Join us, see great speakers, have lunch with other members at lunch (if you’re meeting us in person), and vote for the Plant of the Year!

Nominees for 2023 Rare Plant of the Year

Text by Bobbie J Herbs

Phacelia bipinnatifida

Purple or Fernleaf Phacelia

Found in rocky forests and along stream banks, this biennial forb is listed as Endangered in New Jersey by the USDA NRCS. Purple phacelia blooms in Spring and carpets the ground in 1 – 2’ tall blue to lavender flowers. The flower has a five-lobed corolla with a distinct white star-shaped center and prominent stamens. Once classified in the Boraginaceae family, they are now classified in Hydrophyllaceae.

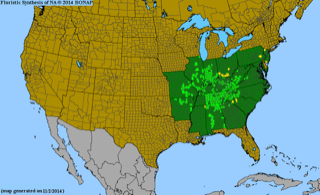

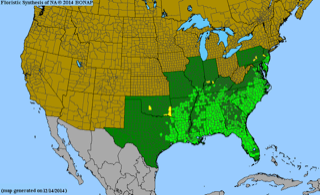

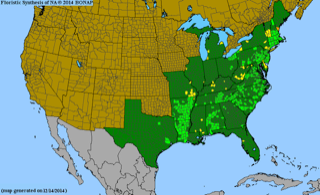

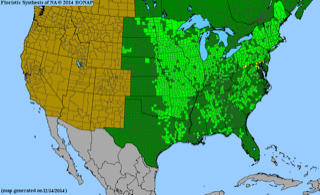

Fernleaf or Purple phacelia, as it is commonly called, ranges from New Jersey south to Georgia and west to Missouri and Arkansas. The species prefers moist soils with dappled deep to partial shade.

Sometimes confused in the wild with Eastern Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum), Phacelia bipinnatifida has larger and more basal leaves. The leaves are fern-like and, as in the specific epithet, bipinnatifid or doubly pinnate. The leaf blades can be 5” long and 3” across. Hairs are on petioles and leaflets, with the earliest leaflets having silver blotches. Blooms in racemes of 4-12 flowers arise on tall stems and last for weeks. Flowers attract solitary bees Andrena lamelliterga, Andrena phaceliae, and Hoplitis simplex.

This is one of those rare plants that is easy to propagate from seed and grow in your shady garden, and some say it is deer-proof. If you are patient, and despite the biennial nature of the plant, you will find seeds germinate each year providing a consistent annual floral display. The leaves of the first-year basal evergreen rosettes make a lovely green or living mulch. The second year, ½ inch blooms appear and linger for weeks in late spring. Once they go to seed, you have the start of a new crop of phacelia. If you plant pots of Phacelia, keep the soil from the pot, it may have a seed bank that jump-starts your annual display of this biennial plant.

Photo credits: Hubert and Millie Ling

Claytonia virginica var hammondiae

Hammond’s Spring Beauty

Claytonia virginica, Spring Beauty, can be found along roadsides and woodland edges in New Jersey. The beautiful flowers with pink guides for early and small pollinators and pink stamens open on a sunny day and remain closed at night or under cloud cover. There are two forms of Spring Beauty that feature yellow. Found in Pennsylvania and Maryland is a pale-yellow form, var. forma lutea. The rarest form, and classified as Endangered in New Jersey by the USDA NRCS, is Claytonia virginica var. hammondiae. This is one of the nominees for the Native Plant Society of New Jersey’s Plant of the Year.

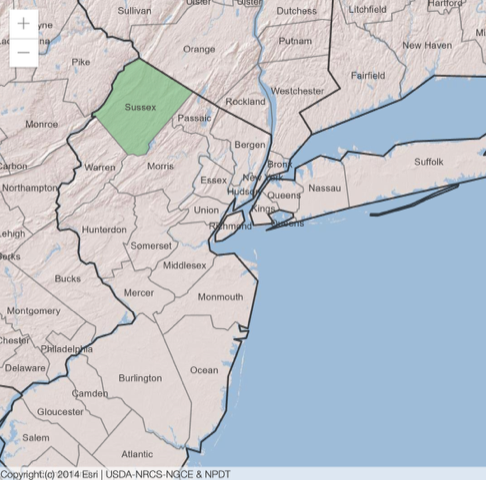

Claytonia virginica var. hammondiae, or Hammond’s Spring Beauty is found in exceptionally wet and acidic areas on the Kittatinny Mountains of Sussex County. This is the single location for this species, although some speculate it may also exist in Eastern Pennsylvania.

Hammond’s Spring Beauty is distinguished by bright yellow petals, orange nectar guides and white anthers. Smooth, grass-like leaves come in pairs and occur halfway up the stem. This is a low plant offering flowers on a 4-16” stem. A spring ephemeral, the plant disappears after the seed capsule ripens in early summer.

Discovered by Emilie K. Hammond more than five decades ago, the naturalist noticed something odd about this field of flowers. They reminded her of common Spring Beauty yet were yellow in color.

At the time, Hammond reported her findings to the Brooklyn Botanical Garden where it was categorized as another Spring Beauty. Years later David Snyder, former NJ state botanist, investigated further and was astonished by every bloom being yellow with no other flower color variations in the field. It was then, that the Nature Conservancy took note and purchased the 77-acre tract in the 1990’s.

This tract is the ‘only place on Earth’ Hammond’s Spring Beauty exists. Quoted in an article for northjeresy.com by James M. O’Neill, May 12, 2017, Scott Sherwood the land steward for several preserves owned by the Nature Conservancy stated, “This meadow is a rare inland acidic seep. The groundwater comes up out of cracks in the bedrock and runs along the top of the bedrock. The water is pretty acidic, with a pH of 5.5 or so.”

Second photo credit: Jim Wright

Trollius laxus ssp. laxus

American or Spreading Globeflower

Found in calcareous (alkaline) cool, wetland swamps, bogs, and fens, American Globeflower is a herbaceous perennial that enjoys open areas without tree and shrub competition. The yellow flowers are unique to the eastern subspecies laxus. A western subspecies (ssp. albiflora) blooms white in the Rocky Mountain states.

Flowers blooms in April with yellow or cream-colored petals and sepals. On terminal stems, the five to seven showy sepals comprise 2” wide flowers that rise five to 20 inches off the ground. Flowers hover above lobed leaves that are three to five inches across. As a member of the Ranunculaceae family, the flowers resemble our common buttercup and can be confused with Caltha palustris (Marsh-marigold) also at home in wetlands.

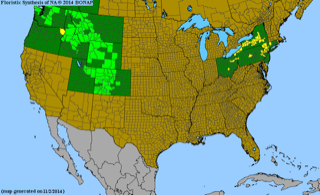

Populations range from western Connecticut and northern New Jersey, through central New York, western Pennsylvania, and northeastern Ohio, yet have dwindled in most states due to changes in local hydrology and watersheds related to human development. Some scientists have cited succession as a factor in their demise, but this has been disputed. The last population observed in Bergen and Passaic Counties date to the early 1900’s. In 2010 the NJ Department of Environmental Protection discovered a large population within the boundaries of a Natural Lands Trust property in Sussex County.

According to the USDA, NRDC Plants Database, Trolius laxus ssp. laxus is Endangered in the following states: Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. It is categorized as Rare in New York where several populations exist in counties from the Bronx to Buffalo.

Photo credits: Hubert and Millie Ling

Lilium philadelphicum var. philadelphicum

Wood Lily

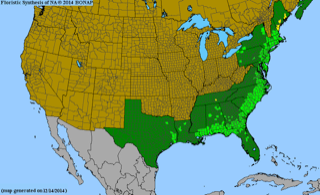

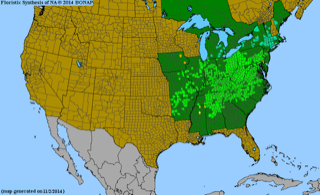

Wood Lily is the most widely distributed of our native true lilies in North America. Across its range there are several varieties, including our regional variety var. philadelphicum. Others in the more western regions are var. andinum and var. montanum. Variety philadelphicum is generally understood to range east of the eastern border of Ohio through the Appalachian Mountains and into the eastern coastal states.

Lilium philadelphicum var. philadelphicum is rare in the eastern portion of its range and is designated as Endangered in New Jersey. Its rapid decline is due to the loss habitat and the increasing number of white-tailed deer. According to Mark W. Skinner in Flora of North America (vol. 26), one of the more reliable places to find this plant is along powerline right of ways.

The variety philadelphicum varies in stature from the western variety with stem heights of 32 inches compared to 24”. It also has 2-5 whorled leaves, averaging 3.8”, with longer and wider leaves averaging nearly 3 inches long and ½ inch wide. Variations in stature, flower size and fruits appear due local cultural differences and soil moisture. Larger plants are typical of moist woodlands and fringes.

This lily arises from chunky bulbs one to two inches below the soil surface. Flowers raise their faces to the sun, as compared to other true lilies that nod. This plant has an umbel with 1 to 6 flowers with 6 red-orange to red-magenta tepals (3 sepals and 3 petals in each flower) which are all slightly recurved. Nectar guides are yellow to orange and spotted maroon and the plant has maroon anthers. Blooming in late May through August, the flower’s natural habitat is open woods, thickets, and barrens. The flowers are pollinated by Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papillo glaucus) butterflies. It is also visited by hummingbirds, resulting in minor pollination.

Native American tribes had various uses for this plant: tonics, poultice, and decoctions of the whole plant were used for curing colds to shedding afterbirth. Because of their great rarity no wild lily should be disturbed in the wild.

Photo credits: Hubert and Millie Ling

Nominees for 2023 Backyard Perennial of the Year

Text by John Suskewich

Clethra alnifolia

Summersweet, pepper bush, sweet pepper bush

That late August scent of summersweet and cedar that a south wind sends up my way in Northern New Jersey is the essence of the Pine Barrens. Summersweet, our native clethra, is a godsend to the late season garden, with that heavenly scent and beautiful panicles of white to pink flowers. Clethra is also known as pepperbush, because the seed capsules resemble pretty small peppercorns, and sweet pepperbush, because somebody couldn’t make their mind up which feature they liked best. If you are ever stuck in traffic on the Garden State Parkway south of milepost 82 you’ll see it growing profusely in its native habitat just beyond the shoulder. Summersweet prefers sites like those open swampy woods, but this medium sized, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub can grow in a variety garden conditions, except bone dry.

Clethra is the namesake of a small plant family, Clethraceae, which is related to ericaceous, usually acid-loving plants like rhododendron and mountain laurel. It will sucker around, and make a nice patch, and in the fall its foliage looks like a schmear of honey mustard in the border.

Summersweet is late to leaf out. In early spring it still looks like sticks, so be patient.

Bees are bedazzled by those fragrant flowers, butterflies sup on them, and birds forage on the seed capsules, which persist into winter. Sedges and ferns are natural companion plants.

Summersweet is a medium-sized New Jersey native shrub, usually 3 to 5 feet tall where it’s happy, with about that in spread if it is suckering with abandon. Digging up those growths is an easy way to propagate it. Move them around the yard or share them with friends and neighbors.

Clethra makes a beautiful hedge, naturalizes easily, and makes an essential woody plant component to a rain garden.

This native shrub deserves its place on the plinth as a garden-worthy plant because of its four-season interest, adaptability to many different sites, and that unique and penetrating fragrance.

Photo credits: Bobbie J Herbs

Sedum ternatum

Woodland Stonecrop

Woodland stonecrop is one of the few garden-worthy succulents native to the American northeast. This diminutive plant grows in both wet conditions like stream banks and dry ones, such as rock ledges but is most reliable in a well-drained spot. In the garden it is especially useful as an evergreen groundcover in partial shade, spreading by stem rooting until it forms a resilient green mat.

Stonecrops are in the great succulent family Crassulaceae, distinguished by their fleshy leaves. Woodland stonecrop is rather cute, its whorls of leaves set in threes daintily around the stem, and the white flowers like sparkling stars rise a few inches above the foliage in spring.

These attract bees and many butterflies, among them hairstreaks and elfin butterflies – species becoming rare in New Jersey primarily because of suburban development. Gardening with woodland stonecrop is one way to sustain these imperiled critters.

Woodland stonecrop grows only a few inches high and wide, but when naturalized as a ground cover the planting can become a nice sized patch. Unwanted plants are easy to pull up, so it is easily passed along in a plant swap. Because of its willingness to spread, low height, and ability to thrive in thinly soiled xeric conditions, it is often used in green roof plantings. This little plant is a real workhorse.

Its uniqueness as a native succulent ground cover that also tolerates some shade and wet makes woodland stonecrop a valuable addition to the perennial border or rock garden.

Photo credit: Toadshade Wildflower Farm

Itea virginica

Virginia sweetspire

Native plant gardeners prize Itea virginica, Virginia sweetspire because of its true four seasons of interest. In spring, this mounding deciduous shrub with arching stems puts back on its jacket of bright green foliage. Bottlebrush racemes of fragrant white flowers follow in early summer and, in the fall, the foliage colors up to a beautiful red burgundy. This autumn foliage persists deep into winter. This year, now mid-February, in our garden most of the garnet leaves are still there, along with its bright red twigs.

Iteas are one of only two genera in the plant family Iteaceae. The “sweet” component of its common name refers to the well scented flowers, which when the plant is happiest can almost cover the foliage and attract bees, butterflies, and humans who adore fragrant plants. This sweetspire is a very low maintenance shrub, with few pest or disease problems. With a tendency to sucker, landscape designers use it for erosion control, in rain gardens, and naturalizing in wildlife gardens. In a home garden, it fills up space handsomely and quickly without running amok.

Virginia sweetspire usually grows three to five feet high and is a fairly low maintenance plant.

Native to northeastern woodlands and swamp edges, it flowers especially well in part shade.

This shrub has been found to exhibit good deer resistance. As with the clethra, the suckers make it easy to propagate and passalong.

This is another essential shrub to use in any garden featuring New Jersey native plants. It is strongly recommended for its ease of maintenance, beautiful and fragrant tassels of flowers, and

The rich coloring of its autumn foliage.

Photo credit: Bobbie J Herbs

Pycnanthemum muticum

Clustered Mountainmint

All of the mountainmints have at least one outstanding trait, but Pycnanthemum muticum, probably the most commonly available, has several. It spreads, but not maddeningly, it has a delightful minty scent, and before its small, pink flowers appear in mid to late summer it develops pale bracts that give the whole plant a very ethereal look. Those bracts persist into fall, making each stem look as if the tip were a silvery-white poinsettia cutting. This is a very low-maintenance native perennial that naturalizes happily and tolerates almost any conditions except prolonged drought or deepest shade. It is very useful for its end-of-the-season impact in the garden.

There are many species of mountainmints native to New Jersey. Like its cousins in the plant family Lamiaceae, the mints, clustered mountain mint will spread, but this tendency can be easily thwarted with a little root pruning with a small spade in the spring. Planting it will have a host of beneficial insects, like ladybugs, hosanning you just before they start to attack their next meal of aphids. It is an important nectar source for bees, butterflies, and other pollinators and is very deer resistant. Mountainmints are another important plant in the ethnobotany of Native American who used it to treat fevers, GI issues, and other physical bugs. That mint taste makes for a pleasant herbal tea.

This two to three-foot perennial usually becomes a clump probably twice that in width. The ovate rounded, pointy leaves are deep green throughout the growing season. In the wild, clustered mountainmint grows in fields and woodland edges and is a fine addition to a meadow garden but is so adaptable it can even be used in a rain garden. Because its runners root so readily, propagation is easy by digging up its offsets.

We recommend this native plant for its late-season beauty, ability to naturalize easily, and importance for insects and other wildlife.

Photo credit: Toadshade Wildflower Farm

Zizia aurea

Golden Alexanders

Golden Alexanders is a highly recommended New Jersey native perennial, easily grown, readily available at many garden centers and nurseries, and well-behaved in the border. Because it blooms after the glorious burst of early ephemerals, golden Alexanders provides a splash of yellow in late spring before the rush of summer flowers appears. It is very adaptable to soil types, moisture requirements, and light, and will gradually make a clumping colony by self-seeding. Some may think that golden Alexanders can be a tad sprawly, especially in shade, but I think of it as just behaving like a very laid-back plant

The genus Zizia is part of the large plant family Apiaceae, the umbellifers, which includes parsley, dill, celery, and Queen Anne ’s lace. Its common name derives from its resemblance to an old-world herb called Alexanders, which doesn’t honor Alexander the Great but as so often the case in the world of common plant names is a medieval corruption of some Latin terms. Indigenous people used it to treat fever and headaches. Golden Alexanders is the host plant for Black Swallowtail caterpillars (the NJ state Butterfly); it is to them what mac-n-cheese is to 11-year-olds, the mainstay of their diet. Many other butterflies and insects, as well as short-tongued bees, nectar at the flowers.

Golden Alexanders is a plant of medium stature, growing one to three feet high with a similar spread. This plant often repeats bloom, extending its flowering season sporadically thru summer, and after the blossoms fade, the semi-evergreen parsley-like compound foliage stays bright green until darkening to purplish with cooler weather. It usually self-seeds, but not bullyingly. To propagate the seeds yourself, it will need a few months of a cold period before germinating in a milder temperature.

We recommend this native plant for its ease of cultivation, gentle spread, season of bloom, and importance for pollinators and other wildlife.

Photo credit: Toadshade Wildflower Farm